The Great Decouplings

What happens when things snap apart?

One Particular Decoupling

August 15, 1971 is a date we don’t speak about as often as we should. That week, the Bee Gees had yet another number one Billboard hit. The talked-about summer blockbuster was The Omega Man.

And something else happened. Richard Nixon announced that the US dollar would no longer be convertible to gold. This effectively marked the end of what was known as the Bretton Woods system and turned the American currency into a fiat one.

Let’s take a step back. After World War II, as the Allied nations established the new world order, they agreed (in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire—hence the name) that the value of one buck would be backed by precious metals (namely gold). In effect this meant that you, a regular citizen, could at any time ask the government to convert your dollars into actual gold. That’s how you knew the dollar had value.

Yet over the following two-and-a-half decades, the system revealed some fundamental flaws. The most notable was that governments had limited control over increasing the money supply. Because of the fixed amount of gold, more dollars meant less gold per dollar. And so each new dollar necessarily meant the dollar was worth less. This led to devaluation, inflation, and other economic woes.

The solution was that 1971 announcement. The dollar’s value would be innate, backed by the promise of its worth by the United States government, rather than by any finite natural resource. In other words, the source of the dollar’s value became… the dollar’s value.

The ouroboros, a dragon eating its own tail

There are two ways to think about what could have gone wrong with this decoupling of the US dollar from gold.

First, you might have fallen into the camp of those who believed that gold was the thing with value. Gold is scarce; therefore it has value. That value existed long before the advent of currency. And that value will survive the decoupling of currency. All the while, the dollar could sink without being tethered to its lifeline.

But you also might have fallen into the camp that believed that gold was nothing more than a representation of value created elsewhere. Gold, by itself, has no intrinsic value either. Value comes from the perception of value. Lots of things are scarce, some much more scarce than gold. So gold, in an of itself, is not special beyond our common understanding that it is special. This camp might therefore believe that the decoupling would cause the dollar to rise and gold to fall.

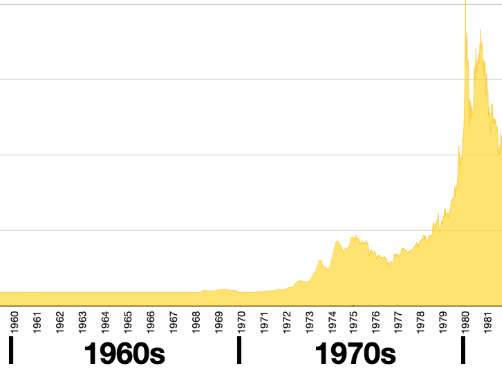

Here’s what actually happened in 1971. First off, the price of gold—which was previously fixed to avoid wild speculation on our currency—was now free to skyrocket:

Interestingly, since 1980, the average price of gold has actually changed very little when adjusted for inflation. And so the market not only quickly aligned on the inherent value of gold; it also preserved that value over a period of almost fifty years. This explains why gold is often seen as a hedge. Its value is, for all intents and purposes, assured.

And what of the dollar? That question is a bit trickier, as it’s not immediately obvious which metric one can use to value a currency. One option is looking at the exchange value of the US dollar relative to another stable currency.

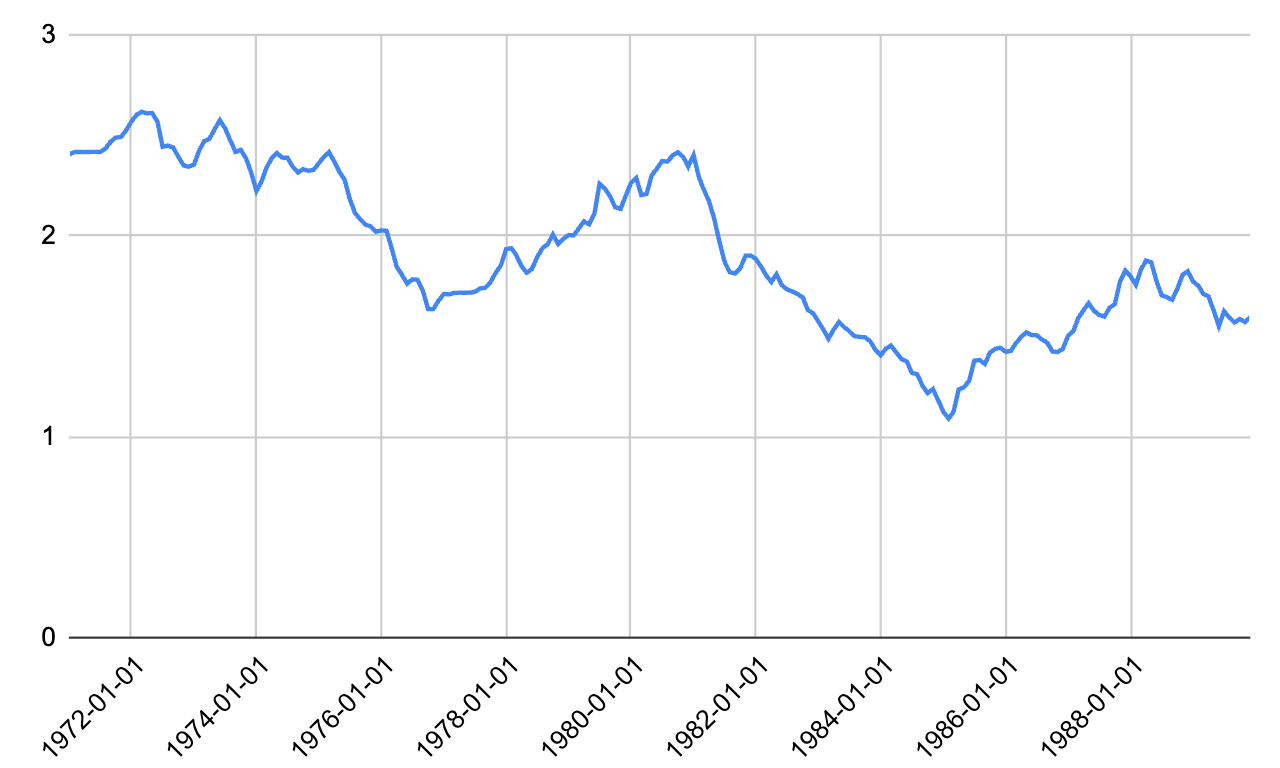

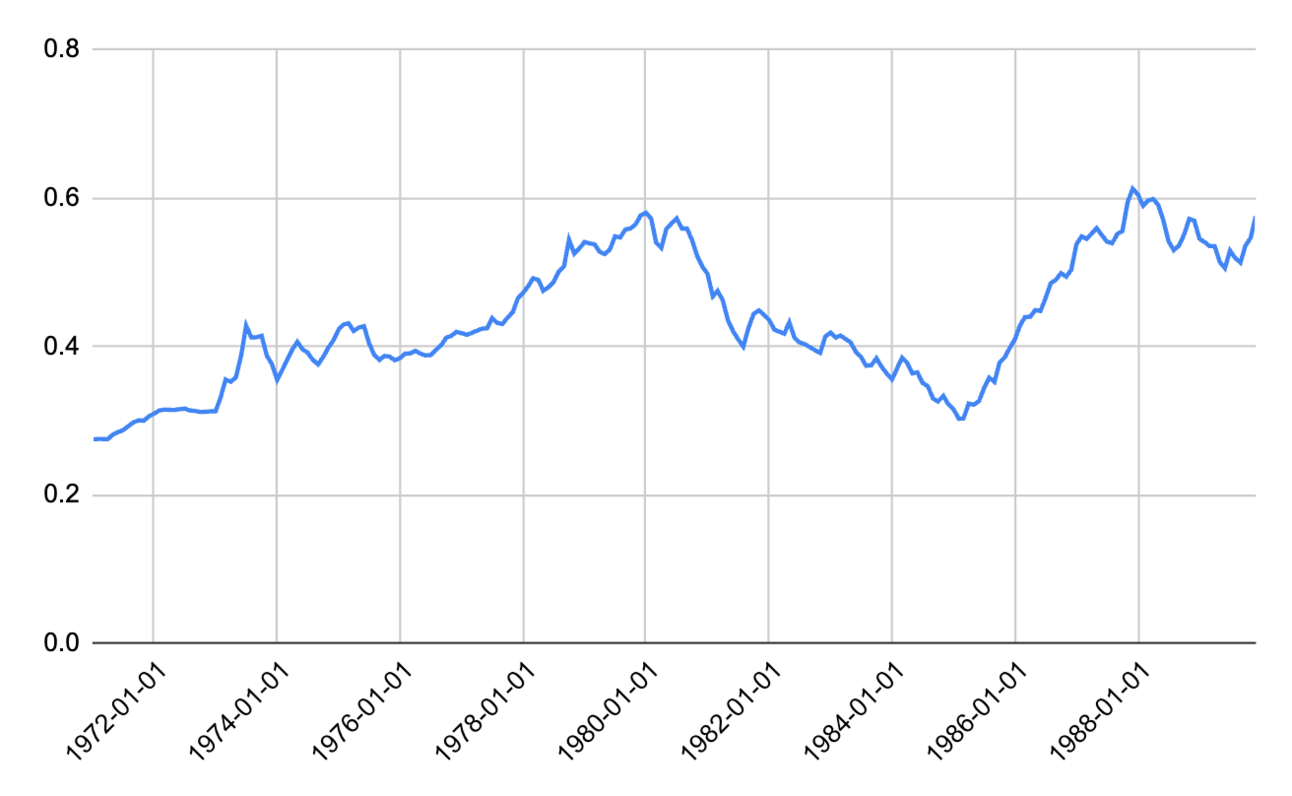

Relative to the British pound, for instance, the US dollar became more valuable:

USD/GBP; lower means a “stronger” dollar

Whereas relative to the West German Deutsche Mark, it became weaker:

USD/DEM; lower means a “stronger” dollar

The key takeaway? Neither the gold alarmists nor the dollar alarmists had it right. Over a sufficiently long enough timeline, gold retained its value, and the US dollar grew stronger as the reserve currency of the world.

Is this the greatest historical example of 1+1=3? Or rather, because the sum of the parts were stronger than the whole, 1+1=1.5?

Other Decouplings

We live at the fascinating crossroads of numerous other “decouplings”. These seismic shifts in how the world works began within the last few years and will have enormous repercussions on future generations. We just don’t yet know what those repercussions will be.

What happens when two things that have always been tightly coupled suddenly snap apart, as the dollar and gold did in 1971? How do we make sense of the garden of forking paths before us?

Here are a few such inflection points we’re living through:

Work decoupled from location

2020 marked the moment when humanity realized that a person’s job need not be fastened to where he or she was physically located. Entire industries—notably services—went from in-person work to Zoom and Hangouts. And while there remains a strong push to return to office five days a week, it’s hard to imagine society suffering the collective amnesia necessary to forget the many hours lost commuting, the many dollars spent on unused office space, the candidate pool made available by no longer geo-restricting hires, and so on.

Which of these two forces wins out in the end: offices or geographic freedom?

Money decoupled from banks

The crypto fad of three years back may have faded from most of our minds day-to-day, but the industry is still booming. Strip away fads such as non-fungible tokens, and you’re left with a hugely disruptive asset class that shows very few signs of going away.

Price of Bitcoin over the last five years

What happens when traditional currency and newfangled currency go head to head? What happens when the value of Bitcoin as a store of value continues to rise? And what will happen in the year 2140, when the very last Bitcoin will be mined?

Education decoupled from institutions

While the cost of college degrees goes up and up (adjusted for inflation, tuition has risen about 40% in the past 20 years), the availability and ubiquity of learning resources online has grown by orders of magnitude.

Another way to phrase this: The cost of formal education is skyrocketing. The cost of informal education is plummeting.

One can think about this as the decoupling of education from institution. But one can also position it as the decoupling of education from learning. The former, as I’ve written before, is a limiting and often antiquated term. The latter, on the other hand, is what we do each and every day, all day long.

Humanity decoupled from creativity

And of course, there’s AI. Another day, another model, and another way to ask ourselves the question of: What happens when much of the world’s creative output is no longer made by human beings? Will it devalue human-made art because the cost of personalized art will drop to zero? Will it increase the value of human-made art because of its uniqueness in a flood of lower-quality content?

I fall in the latter camp. Honestly, as a human, I think it’s my duty to believe that. Otherwise, what are we all fighting for?

Reminds me of a classic line from The Office.

If I can't scuba, then what's this all been about? What am I working toward?