Can We Talk About Homework?

...and where we go from here?

The concept of “Homework” seems old as time itself. As long as people have been taught, they’ve been given assignments to complete out of school…

…except, not quite. In the United States, it wasn’t until the 1950s that homework became commonplace. The motivation was geopolitical: Americans wanted to stay ahead of the competition (the Soviets), so they devised a way to turbocharge the learning of the next generation.

It’s therefore worth starting any conversation about the future of homework by addressing upfront that there is nothing precious or primordial about homework at all. It’s a recent phenomenon.

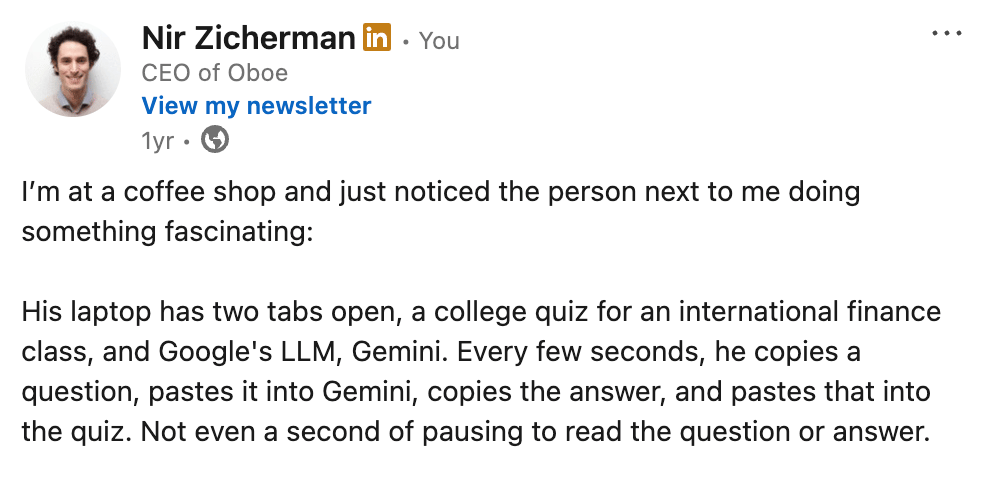

We’ve all now seen the tip of an iceberg: the impact of large language models on formal education. Last year, I posted this anecdote, which continues to terrify me by revealing how broken the current state of homework is:

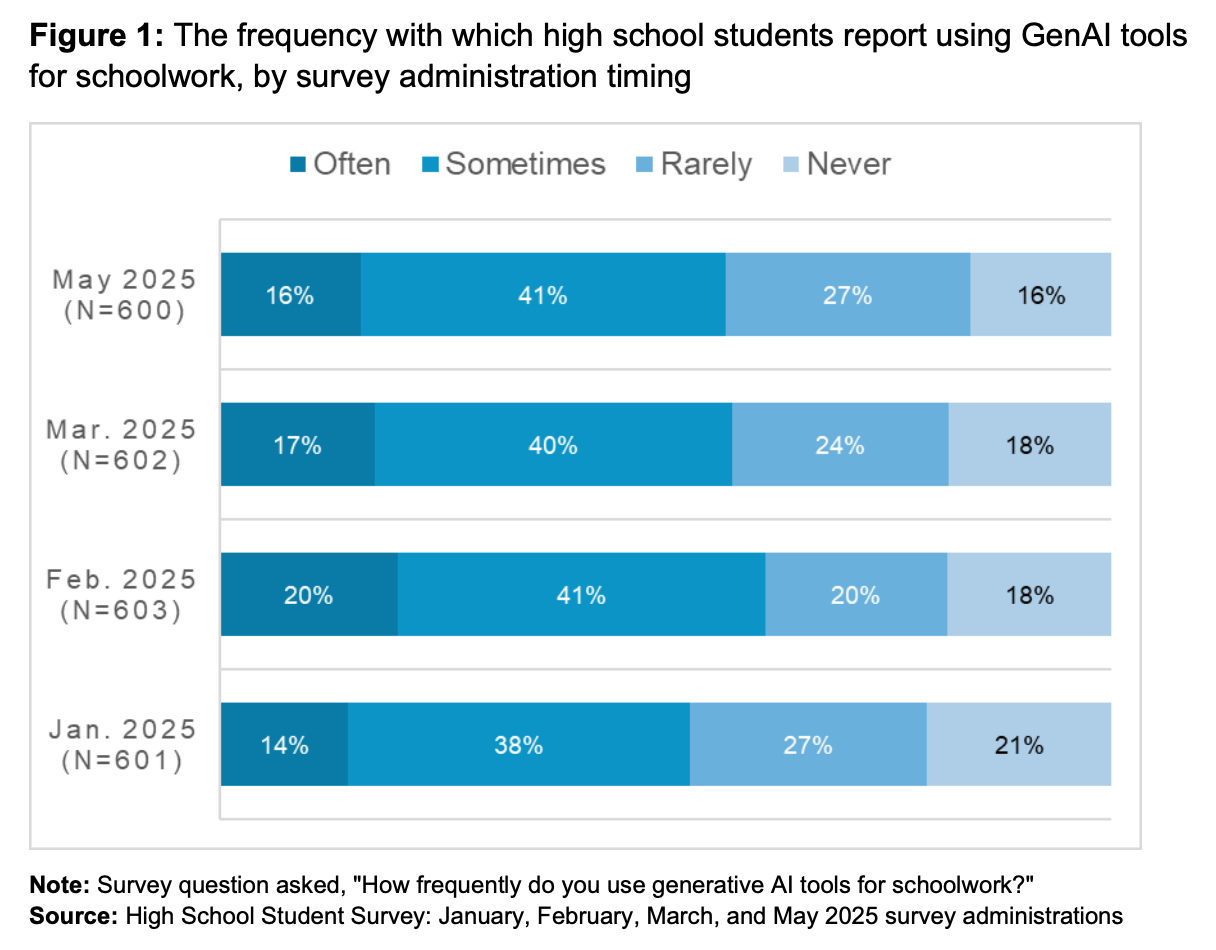

Several recently published reports validate the trends. Take this report from the College Board, which shows that only 16% of high school students never use generative AI tools to at least help with their schoolwork. And this is only three years after the scaled advent of this technology.

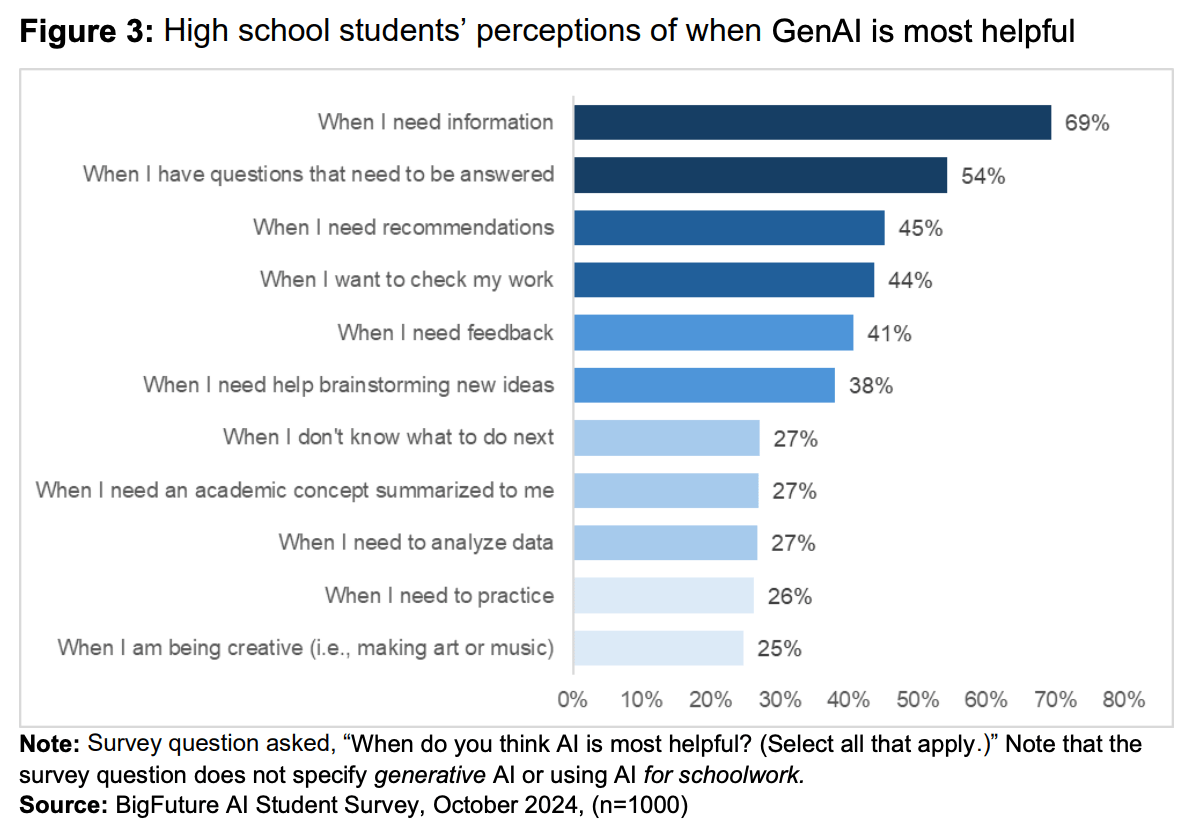

When asked what purpose these AI tools serve, the students gave these answers:

I can’t help but notice that the most likely answer (and the most alarming one) was not even given as an option to those surveyed. That second-most-common answer, “When I have questions that need to be answered” is a euphemism, isn’t it? The true phrasing that should have been offered as an option is: “When I need to do my homework.”

So let’s take a step back and explore homework. Why is it given, where is it going wrong, and where do we go from here?

The Purpose of Homework

Take-home assignments are intended to help teach. But what is it about them that serves a pedagogical benefit?

Homework today is typically meant to reinforce. The sheer repetition of an action (particularly one that requires active thinking) causes neural pathways to strengthen that otherwise wouldn’t have. Perhaps in the 1950s, we Americans fundamentally believed that this would give our kids a leg up over their Soviet counterparts. Doing assignments that reiterated what we’d learned in school would make us all smarter.

But we’d be naive to think that the only reason homework is assigned today. We live in a world governed by economic incentives, with grades and rankings and college admissions. Homework provides checkpoints for how hard a student is working, and that’s as important an input for a teacher (and for the job market) as the underlying knowledge itself. (We’ve all heard the expression “A for Effort”…)

Let’s call this second reason for homework Proof of Work. That’s a term of art borrowed from the world of cryptocurrency. Newly minted Bitcoin, as an example, is given to the “miner” who is able to prove that they did a certain amount of computational work. Similarly, good grades are given to the student who is able to prove (through completion of their assignment) that they did a certain amount of mental computational work.

At least, that used to be the case. Today, it is so trivially easy with most assignments to cheat your way to completion that Proof of Work is no longer a viable justification for homework. Completion of an assignment is—for all but that 16% of do-gooders—now permanently decoupled from any evidence that work was done.

Proof of… What?

It’s worth restating the core insight: Homework used to be a way of determining a student’s effort. Homework provided evidence of effort. But the cost of effort has now virtually dropped to zero. And so whatever proof homework is providing, it often isn’t of work being done.

Back to the drawing board for society, it seems. It’s time to ask ourselves the question, if homework is no longer correlated to proof of work, what should it be tied to?

Let’s revisit the roots of why homework came about in the first place: A means of reinforcing material. A means of letting us get ahead. A means of leapfrogging the competition (except the competition now isn’t the Soviets; it’s our own inevitable brain rot).

Instead of Proof of Work, let’s consider Proof of Understanding. Let’s ask ourselves: how can we rethink homework from first principles, as a measure of how much a student gets the material.

Proof of Understanding

Clearly, any homework that can be completed by AI fails in a number of ways: First, it does nothing to reinforce the material for the students who cheat. Second, it no longer serves as a valuable tool for assessing/grading/ranking students. And most importantly, it disadvantages honest students who actually do the work without AI, while rewarding those who do use AI.

A system based on Proof of Understanding would address first and foremost the real meaning of understanding:

Understanding is not the ability to produce a correct answer to a known question but the ability to produce a correct answer to an unknown question.

And so the goal of homework should be to develop that ability. It is fundamentally a fight against atrophy. I can think of two parallels:

First, picture the way people have, for decades, exercised at the gym: by applying stress to muscle groups. And what we’ve now done is reduced the resistance to near zero. Or we’ve created a machine that lifts the barbell for you. The consequence: Atrophy.

Second, picture Biosphere 2, an experiment to construct a self-sustaining, self-perpetuating habitat in the 80s and 90s. One of the primary reasons it failed: the lack of wind weakened the trees. Trees need wind to grow strong via the reactive development of stress wood. The consequence: Atrophy.

In other words, if we want to assess how well a student understands material, we need to present them with challenges that distort or compress the material, and put them in environments where they (not their computers) actually tackle those challenges. This would be the anti-atrophy.

I like a teacher who gives you something to take home to think about besides homework.

How can we do that in the age of AI? I can think of a number of ways:

Community accountability - Large college lectures often have follow-up sessions for students in smaller groups (often called sections). It’s in these conversations that the real learning tends to happen, because problems are worked through together, and questions are asked and answered in real time. We don’t offer these types of experiences in most formal education, particularly in high school where they’d be most beneficial. These group settings encourage active participation, reduce the likelihood of cheating, and actually measure individual student understanding.

New live formats - Encouraging students to think on the spot is key for reinforcement. Unfortunately this comes with the downside of added stress. The challenge here is how to introduce a sense of urgency and excitement without the corresponding sense of anxiety that often comes with socratic styles of teaching. (As a former law student, I can attest that those stress-first methods are as terrifying as they are ineffective.)

Raise the effort of cheating - Outsourcing your work (whether to a human or a machine) becomes less attractive when two things happen: First, when it is less viable due to the format of the assignment (such as more live or interactive settings). Second, when it yields lower quality output and thereby reflects poorly on you as a student. To this end, I wonder if we need to place much more of an emphasis on how well assignments are done and significantly less on whether they’re done at all.

What does a combined version of all of the above look like? Perhaps a future like this:

Homework assignments are longer term projects, rather than short term one-off tasks. They should be applications of learned concepts, rather than mere regurgitation. They should be contextualized within challenges that would interest and motivate a student.

The purpose of these assignments is practice, preparation, exploration. It is not evaluation.

Evaluation does not happen on the homework itself, but in settings where true assessment can occur. Namely, live settings with your fellow students and/or teachers.

Realistically, we’re years away from a broad redefinition of homework. Formal education is slow-moving, bureaucratic, and regulated. But individual teachers are not: they’re hungry for new approaches, willing to be flexible, and truly care about the success of their students. And so if we can start the dialogue about all of the above, and start thinking about ways to react to this ever-changing world, it will be a grassroots movement that paves the way for a better future and many well-educated generations to come.

Coda

Do you like puzzles? Do you like free puzzles in your inbox every single day? Consider clicking here to sign up for B Sharp, Oboe’s daily puzzle newsletter. Another form of anti-atrophy.

And if you haven’t tried Oboe in the past few weeks, here are a few exciting changes we’ve recently rolled out:

The ability to create full courses in any language, all from a single prompt.

A complete multi-episode personalized podcast about whatever you want to learn.

A comprehensive final exam about whatever you want to learn.

The ability to download/export all course material for Pro users.

And we have more very exciting changes in the works that are coming soon to an oboe.com near you…